If you think your breasts finished growing when you were a teenager, think again! The complex internal structures needed to feed a baby only start forming when you’re pregnant, and until recently we didn’t even understand how they work.

Apart from buying maternity bras, you may not have given much thought to your breasts during pregnancy. Beneath the surface, however, some dramatic changes are under way. While amazing things are happening in your womb, your breasts are also going through an amazing transformation to get ready for your baby’s arrival. To fully understand what’s going on, we need to go back a bit…

How breasts develop during puberty

Your breasts are constantly changing from puberty to menopause. Unlike most of your other organs, they don’t start growing until hormones released in puberty ‘activate’ them. But even though they might look fully grown after puberty, they’re not yet mature.

“After puberty the breast continues to develop, and at each monthly cycle you add a little bit of secretory [milk-producing] tissue up to the age of about 35,” explains Professor Peter Hartmann, an expert in the science of lactation at The University of Western Australia. “After this age, development plateaus and the breast remains mature, but dormant.”

Your breasts also refresh their own internal cells as part of your monthly menstrual cycle – which is why they may feel tender, sensitive or swollen around the time of your period.1

You may notice your breasts feel a bit lumpy during the first days of your cycle – this is because they’re preparing for the possibility of pregnancy. When your body realises you’re not pregnant, the monthly ebb and flow of hormones begins again.2

Internal breast changes during pregnancy

This cycle is interrupted when you conceive. From the end of the first month of pregnancy, your breasts begin to transform into milk-producing organs.

During this time, your milk ducts increase in number and complexity, and begin branching into an increasingly intricate feeding system. Simultaneously, milk-producing cells called lactocytes start developing within your breasts. And the amount of blood flowing to your breasts doubles during pregnancy – which is why you may see the veins through your skin.3

“When you deliver the placenta, your level of progesterone begins to drop and lactation starts to take off.”

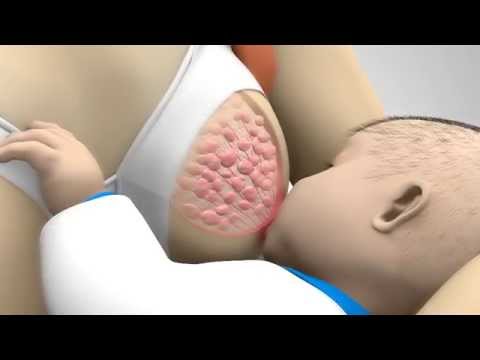

“When you become pregnant, breast development really takes off,” says Professor Hartmann. “When you conceive, it switches on growth of the breast’s existing secretory tissue. You have little branches of bud-like glands in the breast, and when you get pregnant these little buds grow out and form ducts and tiny sacs, called alveoli, to hold the milk.”

This activity inside your breasts can make them feel tingly, sore, swollen or heavy – all early signs of pregnancy. Read How your breasts change during pregnancy to find out more.

The structure of the lactating breast

Believe it or not, it’s only recently that researchers have discovered how this web of ducts within the breast works.

Until this century, most medical knowledge of how breasts produce milk was based on experiments carried out by English surgeon Sir Astley Cooper in 1840.4 He concluded that the ducts stored milk, and released it through 15 to 20 openings in the nipple.

Incredibly, it wasn’t until 2005 that this was investigated further. Research by Professor Hartmann’s colleague Dr Donna Geddes and her team, supported by Medela, revealed that breasts function very differently.5 The ducts are actually small tubes, just a few millimetres wide, that transport the milk rather than store it. Instead, milk is made and collected in the alveoli. These sacs are connected to the ducts by even smaller tubes called ductules.6

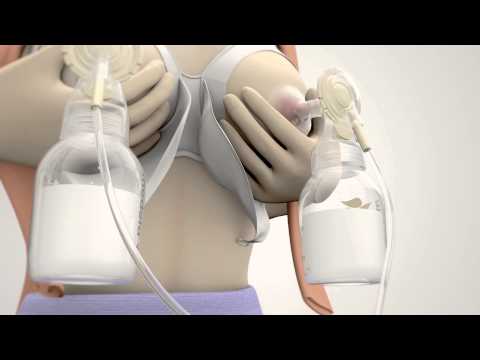

The milk stays in the sacs until the hormone oxytocin is released in your body when your baby starts sucking your nipple. The alveoli are surrounded by muscle cells that contract in response to oxytocin, and it’s these contractions that push the milk through the ducts towards the nipple. This whole process is known as the let-down reflex, and you might feel it as a tingling or whooshing sensation when you start to feed your baby – although some women feel nothing at all.7

The researchers also found nipples have fewer openings than previously thought: usually around nine, and sometimes as few as four. The ducts have to expand by around 68% to accommodate the volume of milk speeding through to this small number of openings.8

“Throughout the duration of breastfeeding, the structure and workings of the breast remain fairly constant until the baby starts to take less milk,” explains Professor Hartmann.

Breasts start making milk during pregnancy

From around halfway through your pregnancy, your alveoli are able to produce milk. Fortunately, your pregnancy hormones prevent them from making lots9 – otherwise they’d be fit to burst by delivery day!

“You don’t want to be producing 800 ml a day while you’re pregnant,” says Professor Hartmann. “So you have a higher progesterone level to prevent milk secretion being activated. Then, when you deliver the placenta, your level of progesterone begins to drop rapidly and lactation starts to take off.”

And if you’re wondering what happens to your breasts once you stop breastfeeding, they go back to a resting state – but not straight away. “When a mother stops breastfeeding completely, it takes a while for the breast to completely switch off – probably a month or two,” says Professor Hartmann. “Human breast milk production takes a long time to shut down, whereas other species are quite quick.”

Eventually, though, your breasts will return to their pre-pregnancy state. Then, if you get pregnant again, the same cycle of growth and development will begin anew.1

Interested in finding out more? Read our free ebook The Amazing Science of Mother’s Milk or see our article Why is colostrum so important?

- Hassiotou F, Geddes D. Anatomy of the human mammary gland: Current status of knowledge. Clin Anat. 2013;26(1):29-48.

- Reed BG, Carr BR. The normal menstrual cycle and the control of ovulation. In: De Groot LJ et al., editors. Endotext [Internet]. South Dartmouth, MA, USA: MDText.com, Inc.; 2000. [cited 2018 April 13] Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279054/

- Geddes DT. Ultrasound imaging of the lactating breast: methodology and application. Int Breastfeed J. 2009;4(1):

- Cooper AP. On the anatomy of the breast. London: Harrison and Co; 1840. 193 p.

- Ramsay DT et al. Anatomy of the lactating human breast redefined with ultrasound imaging. J Anat. 2005;206(6):525-534

- Geddes DT. Inside the lactating breast: the latest anatomy research. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2007;52(6):556-563.

- Kent JC et al. Response of breasts to different stimulation patterns of an electric breast pump. J Hum Lact. 2003;19(2):179-186.

- Ramsay DT et al. Ultrasound imaging of milk ejection in the breast of lactating women. Pediatrics. 2004;113(2):361-367.

- Pang WW, Hartmann PE. Initiation of human lactation: secretory differentiation and secretory activation. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2007;12(4):211-221.